Leigh Marine Laboratory research encompasses advanced study in marine ecology, climate change monitoring, and aquaculture innovation, centered at New Zealand’s first marine reserve. Operated by the University of Auckland, its scientists utilize state-of-the-art acoustic telemetry and physiological testing to understand coastal ecosystems and inform sustainable marine management strategies.

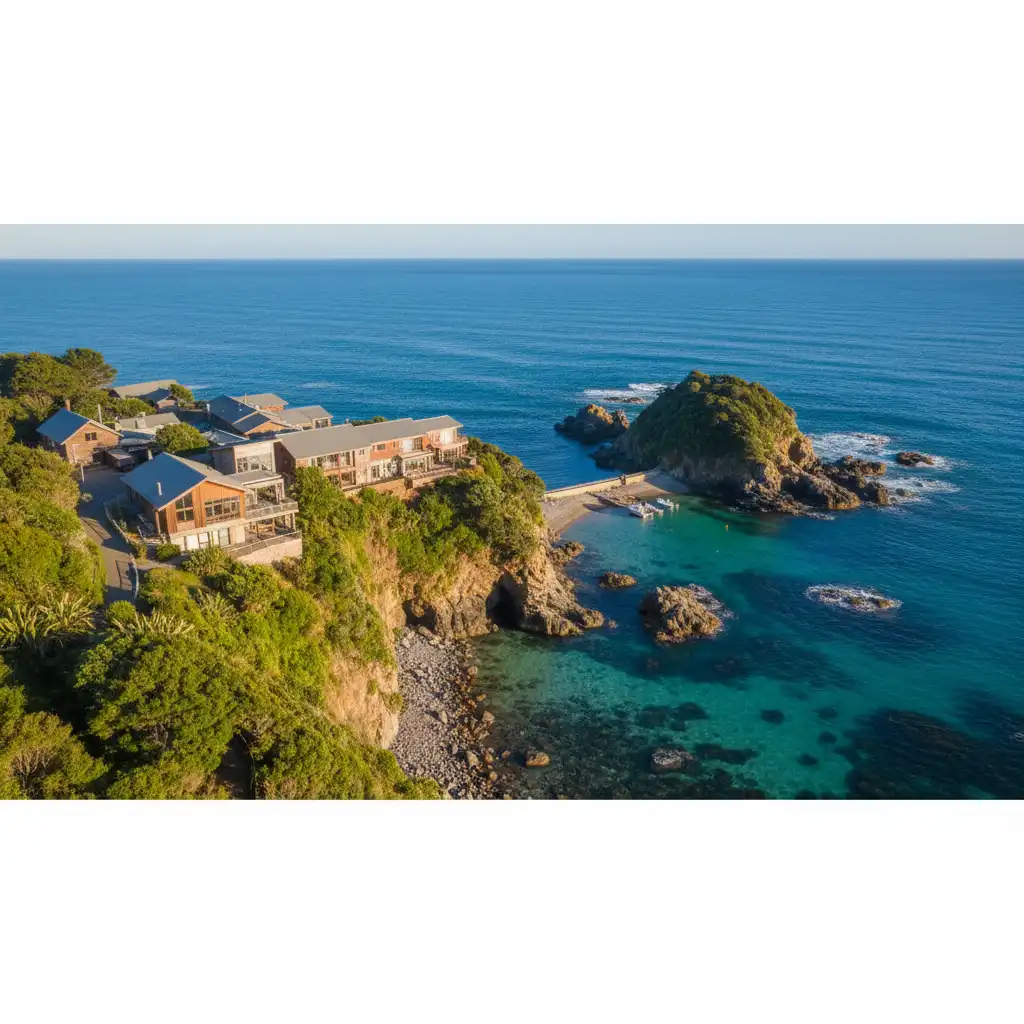

Located on the rugged coastline of Northland, New Zealand, the Leigh Marine Laboratory serves as the operational headquarters for some of the Southern Hemisphere’s most critical oceanographic studies. As a satellite campus of the University of Auckland, it sits adjacent to the Cape Rodney-Okakari Point Marine Reserve—popularly known as Goat Island. This proximity allows researchers immediate access to a protected ecosystem, providing a baseline for what New Zealand’s coastal waters looked like prior to intensive fishing and urbanization.

For stakeholders in NZ marine tourism, policy-making, and conservation, understanding the scope of Leigh marine laboratory research is essential. The data generated here does not merely sit in academic journals; it directly informs how marine reserves are managed, how fisheries are regulated, and how tourism operators can educate the public about the fragile underwater world they visit.

The Hub of Marine Science in New Zealand

The Leigh Marine Laboratory is more than just a collection of buildings; it is a gateway to the Hauraki Gulf and the wider Pacific Ocean. Established in the 1960s, the facility has grown from a modest field station into a world-class research institute. Its strategic location offers a unique advantage: the ability to compare a “no-take” marine reserve directly with adjacent fished areas. This comparative analysis is the cornerstone of much of the Leigh marine laboratory research.

The facility is equipped with running seawater laboratories, allowing scientists to bring the ocean indoors. By maintaining organisms in conditions identical to their natural habitat, researchers can control variables such as temperature, pH, and light to simulate future climate scenarios. This capability draws international scholars to Leigh, fostering a collaborative environment that pushes the boundaries of marine science.

Key Research Projects Conducted Here

Research at Leigh is diverse, spanning from microscopic plankton studies to the behavior of apex predators. The projects conducted here have reshaped our understanding of temperate reef ecology.

Spiny Lobster (Crayfish) Rehabilitation

One of the most significant success stories involving the laboratory is the study of the Spiny Lobster (Jasus edwardsii). Before the establishment of the reserve, local lobster populations were decimated. Research conducted at Leigh documented the rapid recovery of lobster biomass within the protected area. Scientists discovered that when allowed to reach maturity, these lobsters play a crucial role in the ecosystem by predating on sea urchins (kina). This predation prevents the formation of “urchin barrens”—areas where kelp forests have been completely stripped away by overpopulated urchins. This trophic cascade research is cited globally as evidence for the efficacy of marine reserves.

Snapper Genomics and Behavior

The Australasian Snapper (Chrysophrys auratus) is a cultural and economic icon in New Zealand. Leigh marine laboratory research has been instrumental in proving the “old growth” value of snapper. Studies here revealed that large, old fish—often found within the reserve—produce disproportionately more eggs and higher quality larvae than smaller fish. This “big old fat fecund female fish” (BOFFFF) hypothesis, validated by research at Leigh, supports the argument that marine reserves act as biological banks, restocking surrounding fisheries through larval spillover.

Kelp Forest Ecology

The kelp forests of the Hauraki Gulf are the engines of coastal productivity. Researchers at Leigh are currently investigating the resilience of Ecklonia radiata (common kelp) to turbidity and sedimentation. With land-use changes increasing runoff into the ocean, understanding how sediment affects kelp photosynthesis and reproduction is vital. This research directly informs land management practices in the catchment areas surrounding the marine park.

The Acoustic Telemetry Array

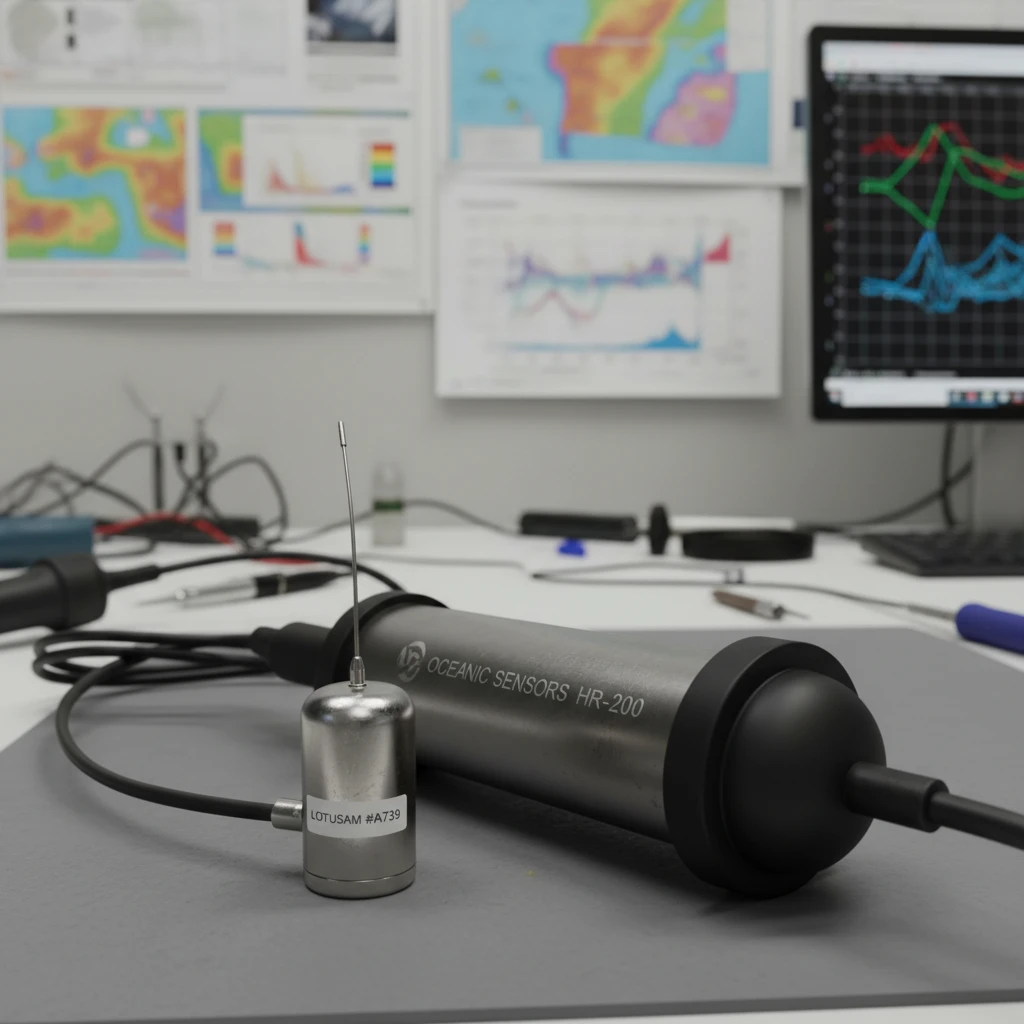

How do we know where fish go when we can’t see them? The answer lies in the advanced acoustic telemetry array managed by the laboratory. This technology represents a quantum leap in tracking marine life and is a flagship component of Leigh marine laboratory research.

How the Technology Works

Acoustic telemetry involves implanting small, battery-operated transmitters into marine animals. These tags emit a unique series of sound pulses—a literal “ping”—that identifies the individual animal. An array of hydrophone receivers is deployed on the seafloor throughout the marine reserve and the adjacent coastal waters. When a tagged fish swims within range of a receiver (usually 300-500 meters), the receiver logs the ID number, date, and time.

Mapping Movement and Home Ranges

Data from this array has provided surprising insights. For instance, researchers found that while some snapper are resident within the reserve year-round, others undertake seasonal migrations. This information is critical for designing the boundaries of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). If a reserve is too small, fish will swim out and be caught, negating the protection. The telemetry data from Leigh helps scientists calculate the optimal size for MPAs to ensure species protection.

Furthermore, this technology allows for the study of circadian rhythms and behavioral responses to environmental stressors. By correlating movement data with environmental logs, scientists can see how storms, temperature spikes, or moon phases affect fish activity.

Climate Change Monitoring and Sentinel Sites

The Leigh Marine Laboratory operates one of the longest-running coastal climate monitoring stations in New Zealand. Since 1967, daily sea surface temperature (SST) records have been maintained, providing an invaluable dataset for understanding local climate trends.

The Sentinel Site Concept

Leigh is designated as a “sentinel site” for observing ocean change. Because the immediate environment is protected from fishing and direct industrial pollution, changes observed here can be more confidently attributed to global drivers like climate change rather than local stressors. This makes the data highly reliable for modeling future scenarios.

Ocean Acidification Studies

Beyond temperature, the laboratory is at the forefront of ocean acidification research. As the ocean absorbs excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, the pH of the water drops. Leigh marine laboratory research utilizes sophisticated flow-through tanks to expose shellfish (like mussels and paua) to the predicted pH levels of the year 2100. Results have been concerning, showing thinner shells and slower growth rates in juvenile shellfish. This research serves as an early warning system for New Zealand’s aquaculture industry, prompting the development of selective breeding programs for more resilient strains.

Public Open Days and The Discovery Centre

Science does not exist in a vacuum, and the Leigh Marine Laboratory places a high priority on public engagement. Bridging the gap between high-level academic research and public understanding is achieved primarily through the Goat Island Marine Discovery Centre.

The Goat Island Marine Discovery Centre

Located within the laboratory complex, the Discovery Centre is open to the public and serves as an educational hub. It features interactive exhibits, touch tanks, and displays that translate the complex Leigh marine laboratory research into digestible narratives. Visitors can learn about the life cycle of the rock lobster, the physics of waves, and the history of the marine reserve.

Public Open Days

Periodically, the laboratory hosts Public Open Days, allowing visitors unprecedented access to the research facilities. During these events, scientists act as tour guides, explaining their experiments and showcasing the technology used in the field. These days are crucial for community buy-in. When locals and tourists see the rigorous science behind conservation rules, compliance and support for the marine reserve increase.

Impact on NZ Marine Tourism

The symbiotic relationship between the Leigh Marine Laboratory and the tourism sector cannot be overstated. The research conducted here safeguards the very asset that tourists come to see.

Science-Backed Conservation as a Drawcard

Goat Island is one of New Zealand’s premier snorkeling and diving destinations, attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors annually. The abundance of fish and the health of the kelp forests are direct results of the protection measures that were established and are continually justified by the laboratory’s findings. Without the ongoing monitoring and defense of the reserve’s integrity provided by the scientists, the ecological value—and therefore the tourism value—of the area could degrade.

Educational Tourism

There is a growing trend in “educational tourism,” where travelers seek to learn about the places they visit. The presence of a world-class research facility enhances the brand of the Goat Island area. Tour operators often cite findings from Leigh marine laboratory research in their briefings, explaining to snorkelers why the snapper are so large or why the water clarity fluctuates. This adds depth to the visitor experience, transforming a simple swim into an eco-tour.

Conclusion

The Leigh Marine Laboratory stands as a pillar of excellence in marine science, offering critical insights that extend far beyond the academic community. From the detailed tracking of fish via acoustic telemetry to the long-term monitoring of climate change impacts, the work done here is vital for the future of New Zealand’s oceans.

For the marine tourism industry, the laboratory is a silent partner, ensuring the ecosystem remains vibrant and healthy. For the public, it offers a window into the underwater world, demystifying the ocean through the Discovery Centre and open days. As environmental challenges mount, the importance of the rigorous, data-driven Leigh marine laboratory research will only continue to grow, guiding us toward a more sustainable relationship with our blue backyard.

What is the main focus of Leigh Marine Laboratory research?

The laboratory focuses on marine ecology, climate change impacts, fisheries management, and aquaculture. Key areas include understanding the benefits of marine reserves, tracking fish behavior through telemetry, and monitoring long-term oceanographic trends like temperature and acidification.

Can the public visit the Leigh Marine Laboratory?

The research labs themselves are generally restricted to scientists and students to maintain controlled experimental conditions. However, the public can visit the Goat Island Marine Discovery Centre located at the facility, and attend specific Public Open Days scheduled throughout the year.

How does the acoustic telemetry array work at Leigh?

Scientists implant acoustic tags into marine animals which emit unique sound pulses. A network of hydrophone receivers placed on the seafloor detects these pings when the animal is nearby, allowing researchers to map movement patterns, home ranges, and migration behaviors with high precision.

Why is Leigh considered a “sentinel site” for climate change?

Leigh has maintained daily sea surface temperature records since 1967, creating one of the longest continuous datasets in the Southern Hemisphere. Its location in a protected marine reserve minimizes local variables like fishing pressure, making it an ideal benchmark for observing global climate shifts.

What is the relationship between the lab and Goat Island Marine Reserve?

The laboratory is situated adjacent to the reserve. The reserve serves as a natural “living laboratory” for the scientists, while the research conducted by the lab provides the scientific evidence needed to manage and protect the reserve effectively.

Does the research at Leigh help recreational fishing?

Yes. Research into the “spillover effect” has shown that marine reserves help replenish surrounding waters. By studying snapper and lobster reproduction within the reserve, scientists demonstrate how protected areas act as nurseries that eventually boost fish stocks in areas open to recreational fishing.