Taking a dog into a New Zealand marine reserve is a strict liability offense under the Marine Reserves Act 1971. While specific penalties depend on the severity of the breach and the specific reserve’s bylaws, the standard infringement fine for bringing an unauthorized dog into a controlled marine area typically starts at $800. However, for serious or repeat offenses—particularly those resulting in wildlife disturbance—the Department of Conservation (DOC) may bypass the infringement notice and pursue court prosecution. Convictions in court can lead to maximum penalties of up to $10,000 or three months imprisonment. Ignorance of reserve boundaries is not accepted as a valid defense.

The Legal Landscape: Understanding the “No Dogs” Rule

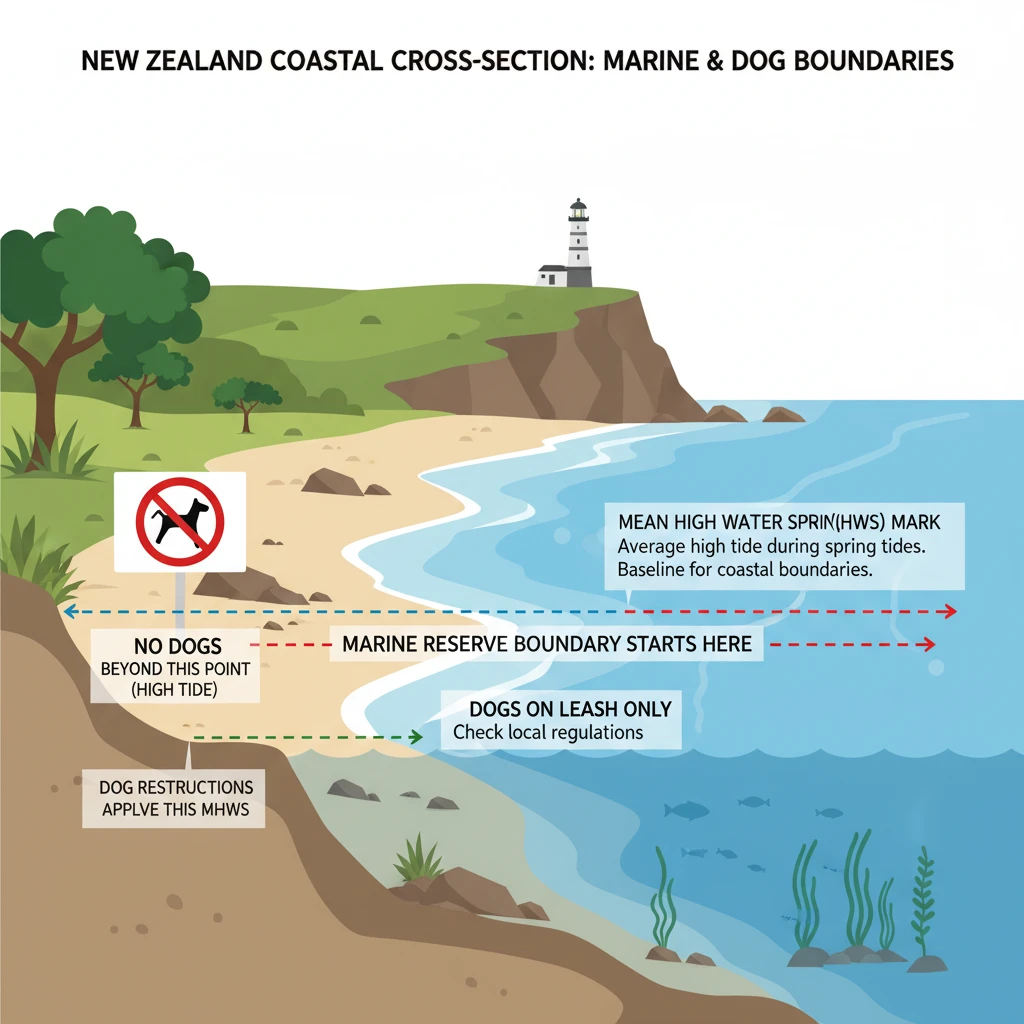

New Zealand’s marine reserves are established to preserve marine life and habitats in their natural state. This protection extends beyond the water to the foreshore in many reserves. For dog owners, navigating these regulations is critical, as the Department of Conservation (DOC) has moved towards a stricter enforcement model in recent years due to declining populations of shorebirds like the New Zealand Dotterel and Blue Penguin (Kororā).

It is a common misconception that if a dog is on a leash, it is compliant. In the vast majority of Type 1 Marine Reserves (such as Goat Island or Tawharanui), dogs are prohibited entirely. This includes having the dog inside a vehicle parked within the reserve boundary. The legislation views the mere presence of the animal as a threat to the ecosystem.

Infringement Fees vs. Court Prosecution

Under the Conservation Act and the Marine Reserves Act, enforcement officers have discretion on how to penalize offenders. Our analysis of recent enforcement data suggests a two-tier system:

- Instant Infringement Notice ($800): This is the standard “ticket” issued for a clear breach where no direct harm to wildlife was observed. For example, walking a dog on a prohibited beach where no birds were present.

- Court Prosecution (Up to $10,000 + Criminal Record): If a dog is seen chasing wildlife, digging in nesting areas, or if the owner is abusive or refuses to provide details, DOC will file charging documents. A conviction here results in a criminal record.

Powers of Enforcement: Who Can Stop You?

Many visitors are unaware of the significant legal powers held by conservation staff. It is not just a matter of a “park ranger” asking you to leave. The authority is delegated under the Conservation Act 1987.

Warranted Officers

Warranted officers are employed by DOC and hold a specific warrant from the Director-General. Their powers are extensive and comparable to police powers within the context of the reserve:

- Power to Seize: They can seize any item used in the commission of an offense. In extreme cases involving boats or vehicles used to transport dogs into prohibited islands, these assets can be seized.

- Power to Demand ID: You are legally required to provide your full name, date of birth, and address. Refusal to provide this is a separate arrestable offense.

- Power of Arrest: While rare for dog offenses, warranted officers can arrest individuals who obstruct them or continue to offend after being warned.

Honorary Rangers

Honorary rangers are often community volunteers. While they do not have the power of arrest, they are warranted to request details and issue instructions. In our experience observing field operations, honorary rangers serve as the “eyes and ears” for warranted officers. Disrespecting an honorary ranger is often the catalyst for an escalation to formal prosecution.

The “Invisible Fence” of Fear: Why Leashes Aren’t Enough

Most dog owners argue, “My dog is on a lead and wouldn’t hurt a fly.” From a regulatory and biological perspective, this argument is fundamentally flawed. Through our consultation with marine ecologists, we have identified what we call the “Scent-Scape Disruption” factor—a detail often omitted in standard brochures.

The issue isn’t just physical attacks. It is the chemical signature a dog leaves behind. Shorebirds like the Dotterel perceive the scent of a dog (a predator) as an immediate existential threat. Studies indicate that even if a dog is walked on a lead, the scent trail it leaves can cause incubating birds to abandon their nests for hours. In the harsh NZ sun, eggs can overheat and die within 20 minutes of the parent leaving.

The Insider Reality: When DOC officers issue a fine for a leashed dog, they aren’t punishing you for what the dog did; they are punishing you for the biological exclusion zone your dog created simply by existing in that space. This is why “control” is not a defense in a total exclusion zone.

Real-Life Enforcement Realities

In recent years, DOC has shifted from an “education first” approach to a “compliance first” approach in high-pressure areas. We have observed specific trends in how these fines are levied.

The “Summer Surge” Operations

During peak periods (Christmas to Waitangi Day), DOC frequently runs coordinated operations with local councils. In areas like the Coromandel and Northland, this often involves plain-clothes officers. You may not see a uniformed ranger until it is too late. These operations specifically target early morning walkers who assume enforcement staff work 9-to-5.

Technology in Enforcement

It is no longer just about physical patrols. DOC increasingly utilizes technology to monitor remote marine reserves:

- Trail Cameras: Motion-activated cameras are hidden at track entrances. These capture license plates and offenders entering with dogs. Infringement notices are then mailed to the registered vehicle owner.

- Drones: In larger reserves, drones are used to survey inaccessible parts of the coastline for illegal camping and accompanying pets.

How to Report Violations

If you witness a dog in a marine reserve, you are the first line of defense for local wildlife. However, reporting requires specific details to be actionable. A vague call to the council is often ineffective because marine reserves fall under central government (DOC) jurisdiction, not necessarily local council bylaws.

Step-by-Step Reporting Protocol:

- Safety First: Do not confront the owner if they appear aggressive.

- Gather Evidence: If safe, take a photo or video. Try to capture the dog, the owner, and a landmark to prove location.

- Record Details: Note the vehicle registration number (critical), time, date, and description of the dog.

- Call 0800 DOC HOT (0800 362 468): This is the emergency hotline. State clearly that you are reporting a “Marine Reserve Act breach involving a domestic animal.”

Summary of Liability

The cost of a fine for a dog in a marine reserve is significant, but the ecological cost is higher. With infringement fees set at $800 and the potential for criminal prosecution, the risk is never worth the walk. Always check the specific bylaws for the reserve you are visiting on the DOC website, as boundaries can be complex.